Presented by IFCFilms, the documentary Lakota Nation vs. United States recounts one of the longest court battles in US history from the perspective of the Lakota Nation. The sacred land, known as the Black Hills, is located in present-day western South Dakota and eastern Wyoming. Since the arrival of Europeans, the land and the Indigenous Americans of that land, have endured conflict, exploitation, and genocide.

Written and narrated by Oglala poet Layli Long Soldier and co-directed by Jesse Short Bull and Laura Tomaselli, Lakota Nation vs. United States details a thought-provoking history of the struggle, from broken treaties to the historic Supreme Court case of 1980, which ruled in favor of the Očéti Šakówiŋ people. Five generations after director Jesse Short Bull’s great-great grandfather Tatanka Ptchela (Short Bull) refused to sign the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty, the ownership of the Black Hills is still under contention and the people are still committed to reclaiming what was taken.

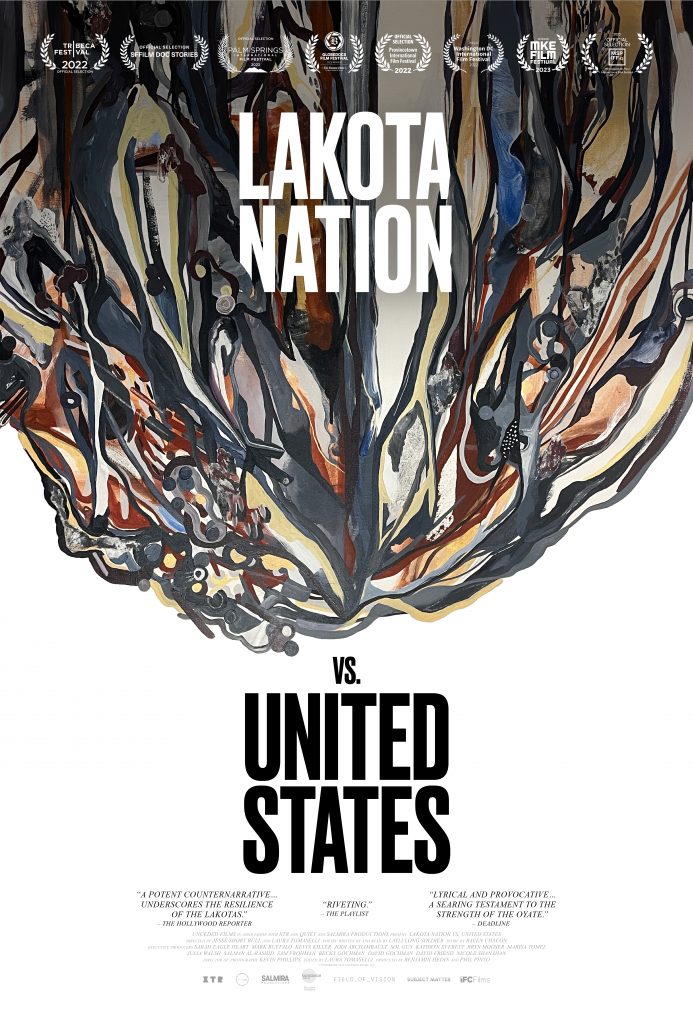

A story without a resolution, the documentary also serves as a love letter to the land itself, whose sweeping vistas and natural beauty demand to be seen on the big screen. Executive produced by allies such as Mark Ruffalo and Marisa Tomei, this cinematic testament to resilience arrives in theaters on July 14th. In advance of the release, Boxoffice Pro spoke with director Jesse Short Bull and director/editor Laura Tomaselli about the origins of the project and the importance of bringing indigenous stories to cinema screens.

How did the project begin and take shape?

Jesse Short Bull: There’s something that I think is bigger than ourselves. One of our producers, Mark Ruffalo, mentioned something about timing. It’s just interesting that the timing is now. Initially, how it started was, one of our producers, Benjamin [Hedin], saw a news article about the court case pertaining to the Black Hills and what is referred to as the Sioux Nation, or what’s correctly known as the Očéti Šakówiŋ. The information that was highlighted in that article [detailed] one of the longest-standing court cases in United States history, a court case that was won by the Sioux tribes [in 1980]. The settlement part of the decision was rejected by the tribes. That article, and the curiosity our producer Ben had, was really the catalyst that started moving everything forward. I had a phone call with Ben and I really came to admire his curiosity for this story. I was hoping that, maybe people across the country who are not familiar with this history, would also find this [story] compelling. And really leaning on my intuition, things just seemed to work out. Very shortly after that, Laura was in the picture. Once I met Laura, and her partner Phil [Pinto], who’s also a producer, it was, ‘We have to do this. We have to do it.’ It’s just been a blessing ever since.

There’s a lot of history to distill into just two hours. How did you work together to define the shape of the story and Laura, in your dual role as the film’s editor, what did that process look like in the editing room?

Laura Tomaselli: I think that was definitely the hardest part of this. One thing that Jesse and I talk about a lot is, how you simplify and fit the story into two hours. Honor it, but still allow it to have an arc, still allow it to move people. It was really hard. We had a first janky cut that everyone was very polite about that was three and a half hours. I think that the hardest part was choosing what to lose. We had two main shoots. What’s crazy is, I totaled this up the other day, we had 15 total shooting days, which is not a lot. I’m not a person that sets out with a huge plan, along the lines of what Jesse’s saying about intuition. The way the film really came together was just sitting with the material, ingesting it and allowing things to rise out of it. Even the names for the [film’s three] sections were things that we were consistently confronted with. Assimilation is probably the easiest one to understand, but Extermination and Reparation came very organically from the pieces in those sections.

Jesse Short Bull: I grew up in South Dakota. I grew up in cattle country, in addition to growing up right next to the Oglala Lakota Nation. I was very familiar with western movies, cowboy movies. What really clicked for me, even prior to meeting Laura, was when she sent me a little teaser of a western [Calamity Jane], where the two characters are singing about the Black Hills in Indian country and mentioning that it’s Indian land. I’d never seen that clip before and I was really taken aback by it. Once I [had] seen how Laura put that clip together, I knew this was going to be fun. And I don’t mean that we took it lightly, because Laura and I both took this very seriously. There was a lot of pressure to make sure that we did this in a good way, in the right way. But also, seeing that clip [from Laura] gave me that movie magic feel, you know?

Laura Tomaselli: There’s no end to the tragic, serious things that happen in the movie. Part of survival is humor. I think for this film to be humorless, would be awful. It’s been great to watch it with a bunch of indigenous audiences that really laugh at some of the things that Jesse’s mentioning, like the musicals, where it’s like, [singing] ‘Indian Laaaand!’. It’s funny, right? And so we bonded over that quickly.

How does film history play a role in, not only crafting the story of the film, but in shaping American perceptions surrounding indigenous people?

Jesse Short Bull: Nick Estes, who we feature in the film, I think really drives this point home. The period of time when westerns dominated the box office, and were front and center in American culture, a lot of those featured stories of fighting Indians. It made the invasion look like self defense. We’re watching these people trounce all over indigenous people’s lands and the bloody conflicts, but yet, in our psyche, we root for the cowboys. That’s why we’re still facing a lot of the dangers that we are today, because of that time.

Laura Tomaselli: I certainly understood there were Native American stereotypes in golden age of Hollywood westerns, but I think a lot of people don’t think about it. It was important for us to show people something that might be familiar and give them added context. I think it also appealed to me to use some of these things–that are like sly propaganda for us to feel okay about living where we live and being who we are–it was important to try and turn some of those pieces for our own agenda. To kind of punk these old things that have been destructive in the past and use them as our own sort of building blocks. Certainly I think that we approached the story as a western. It’s hard not to be in those landscapes and hear the song, hear the twang. But definitely using that film language to attack itself, if that makes sense.

The film also flips the script on the letter ‘X’, how does that significant mark of the past play into the present story?

Laura Tomaselli: I’m glad you asked that, because one of the things about using film language and sort of punking traditional film language, actually came from Layli Long Soldier, the beautiful poet who wrote that poem, “135 X’s”, [and] whose voice is in the movie. When you read her poetry, whether you’re listening to her or you read it yourself, her ability to dissect and break apart the English language–where we put emphasis, what words mean, and what does an ‘X’ really mean–definitely gave us the same license, I think, to use film language in that way. I thought about deconstructing, using those building blocks, but kind of pointing them in different directions. “135 X’s”, that poem she gave us, arrived around a month before the Tribeca [Film Festival] deadline, something really scary. Jesse and I work really well together, and we have a good division of labor, so I could play with that while he was off getting another interview. We were able to make it work.

Jesse Short Bull: It’s looking at language. What does that really mean? What is the weight and breadth behind it? It’s looking at language in a different way.

Speaking of cinematic language, why is it important to have this story in theaters? And for audiences to see history unfold on the big screen?

Jesse Short Bull: A lot of times indigenous issues are way at the bottom of the barrel. Part of that may be designed. It’s a really terrible feeling because, things can be going on in a community, issues and disparities. It [feels] like you’re all alone. Nobody hears you, nobody sees you. Everything that you know doesn’t really exist anywhere–your history. When you go out into the world, it’s hard, because people don’t understand you. They don’t understand where you’re coming from. Having this in theaters, I want people to know about our heroes. A lot of people can, off the top of their head say, ‘Oh yeah, Red Cloud. I know who that is. Crazy Horse. Yeah, I’ve heard of him before.’ But anything in the last 100 years? Who do you know? Who can you reference that has done things above and beyond themselves–who’s served people, who’s helped people? It’s almost like they don’t exist, but they do, and they always have. The blessing of this film is, for a short period of the short time that we all have here on this planet, we really showcase a cross section of the Očéti Šakówiŋ, the amazing, beautiful, heroic people that we have. And how the treaty, how the land, relates to them.

Laura Tomaselli: We thought about Western tropes when making this, but I personally also thought a lot about superhero movies–before we had Ruffalo attached even. I think that the way that any kind of activism is portrayed in the media is normally the inconvenience of people that are parked behind the blockade. I feel like the media typically misunderstands activism. It was really important to me to depict people like Krystal Two Bulls, like Phyllis Young. Krystal climbs the top of the water tower at the end––spoiler alert! She did it. It’s a superhero movie. To what Jesse’s saying, a lot of people that aren’t from Pine Ridge, come to Pine Ridge and see poverty. They come for three days, they do a news story, and it’s about poverty. The thing that was necessary for me to learn, and Jesse was instrumental, is that no one thinks about causation. No one thinks about, ‘Why poverty? Why is it this way?’ Culpability for the situation they’re currently in. It was really important to portray the optimism, the beauty that’s there. I hope that’s what people take away from this film.

What is Landback? And how can non-indigenous people learn more about becoming allies?

Jesse Short Bull: Landback is an amazing concept. Here in South Dakota, the seven tribes of the Očéti Šakówiŋ have a very profound relationship with the land. Landback is a movement to try to restore that. Restore that powerful connection between people and the land. It’s also about holding land in high regard, as even today in the Black Hills, there is still extraction work that is potentially unfolding. It’s hard for our people to watch that happening. If our people had a say in what’s going on in the Black Hills, I don’t see how that could be detrimental to anyone. It’s just taking care of our land. There’s a multitude of ways that it can be done. There’s a lot of public lands in and around the Black Hills. The federal government can definitely move us in the right direction. We’ve also seen people donate land back to the tribes. That’s really remarkable, I definitely think that’s a blessing. In addition, for anybody that would like to advocate or help, as part of the impact of the film, we do have a platform to connect people that’s called BlackHillsJustice.org. I think what you will see is a lot of the Lakota, Dakota and Nakota tribes, reassert their position on the Black Hills and where they stand. Hopefully it’ll be at the Federal level. I think the gears are in motion. I think it’s just a matter of people encouraging their leadership to take a good, strong listen, and when that moment does come, really try to support us.

Share this post